8th-graders train peers to get into high school

Applying to high school in New York City can be a full-time job for 8th-graders and their families. Students who don't have an adult to help them have an even harder time navigating the system—and making the most of their options. Now, in two city neighborhoods, an innovative Department of Education program trains students to help each other through the process.

Modeled after a successful high school college access program, the Middle School Success Centers began as a pilot program on the Lower East Side and in Cypress Hills in late 2013, targeting neighborhoods where students could really use the help.

At IS 171 in Cypress Hills, counselors from the Cypress Hills Local Development Corporation offer intensive high school choice counseling and training for youth leaders in one of the poorest communities in the city. The middle school youth leaders are trained in a summer program and commit to working with their fellow students during lunch hour and after school to help them understand the admissions process and make good choices on their high school applications. They apply for the job and are paid $50 per month.

Youth leader Nayely Vasquez, a rising 8th grader, learned about the program in summer camp last year and was eager to apply to share her knowledge with others. "Some people just want to go to schools that are close to them but they don't fit. We want to help them apply to the proper schools that are the right fit," she said. Others only list schools that their friends are applying to, which isn't a good idea, said her fellow youth leader Britnee Monsegue-Galloway.

Caroline Taveras, an adult counselor at the center who was raised in Brooklyn by immigrant parents, can relate to her students' struggles with the application process. She said that many of the families are first generation immigrants who are reluctant to send their children out of the neighborhood and end up settling for low performing schools. "I can count on one hand the number of times I left the borough before going to college," she said. "This [program] is opening doors for them.

Peer-to-peer training is the most important aspect of the program, IS 171 Success Center Director Parastoo Massoumi explained. "It helps empower students and has totally changed the vibe and culture of the school," she said.

Students at success centers get extensive help both from the counselors and their peers in workshops, one-on-one meetings with students and parents, mini high school directories published by the centers, and in trips to both high schools and colleges. In the past two years, Massoumi said the center has logged nearly 1,000 overall hours of high school admissions counseling. The help they provide goes way beyond what a typical school guidance counselor can do. "One guidance counselor focusing on 250 students is just not okay," Massoumi said.

The intensive approaches seems to pay off.

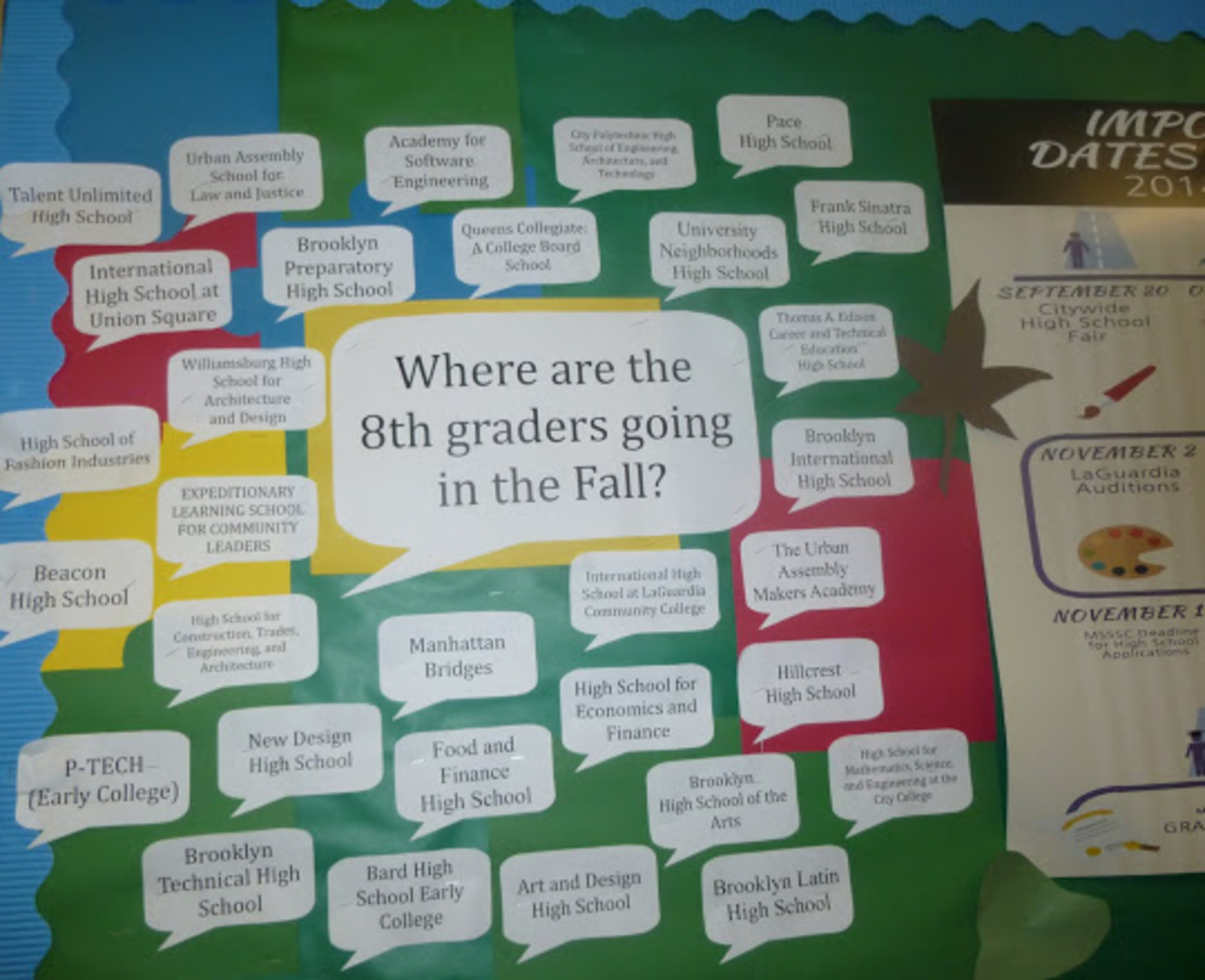

In 2013 before the Middle School Success Center opened, 91 percent of IS 171 8th-graders were matched to a high school in the first round of applications; by 2015, 96 percent of 8th-graders were matched, most to higher-performing schools with higher graduation rates, said Massoumi. Some were accepted by competitive screened high schools in other boroughs, such as Bard and Beacon, as well as several of the specialized and arts high schools.

On the Lower East Side, the Henry Street Settlement runs its Middle School Success Program for three small middle schools in the Corlears complex. About 90 percent of the students qualify for free lunch, few are performing on grade level and most choose to stay in the neighborhood for high school, said Shalema Henderson, the program coordinator.

"Most students are misinformed about the [high school admissions] process or not informed at all, " said Henderson, adding that her school has a high population of English language learners and special needs students. A huge benefit for them, she said, is that the success center counselors take them to high school open houses and tours. Many high schools give priority in admissions to students who actually visit the school, a method called "limited unscreened." If a family doesn't know about these events or doesn't fully understand their importance in the admissions process, a students may lose out on a great high school option.

"This [method] gives preference to families that are super-involved and super-engaged," said Henderson. "Kids can't go on their own. It weeds out kids who could've been a good choice."

Since the program began, Henderson has seen improvement both in the choices that students are making and in the schools they are matched to. All 8th-graders from the three schools in the building were accepted in the first round of admissions in 2015, Henderson said, many to sought-after schools with high graduation rates such as Pace and the High School for Economics and Finance.

This summer some ten students from the building are spending two days a week getting trained to counsel their fellow students in one-on-one sessions and workshops in the fall, as are students at IS 171.

Despite its early success, the future of the pilot program remains in doubt. Department of Education funding for the pilot programs at both sites expires after this school year. Henderson and Massoumi are working together to figure out a way to make the program replicable—if not in all NYC high schools, then at least in the areas that need it most.

"If the system was working well we wouldn't have to exist," said Massoumi. "But the system isn't working well for our students."

Please Post Comments