Can "learning as play" make a kindergarten comeback?

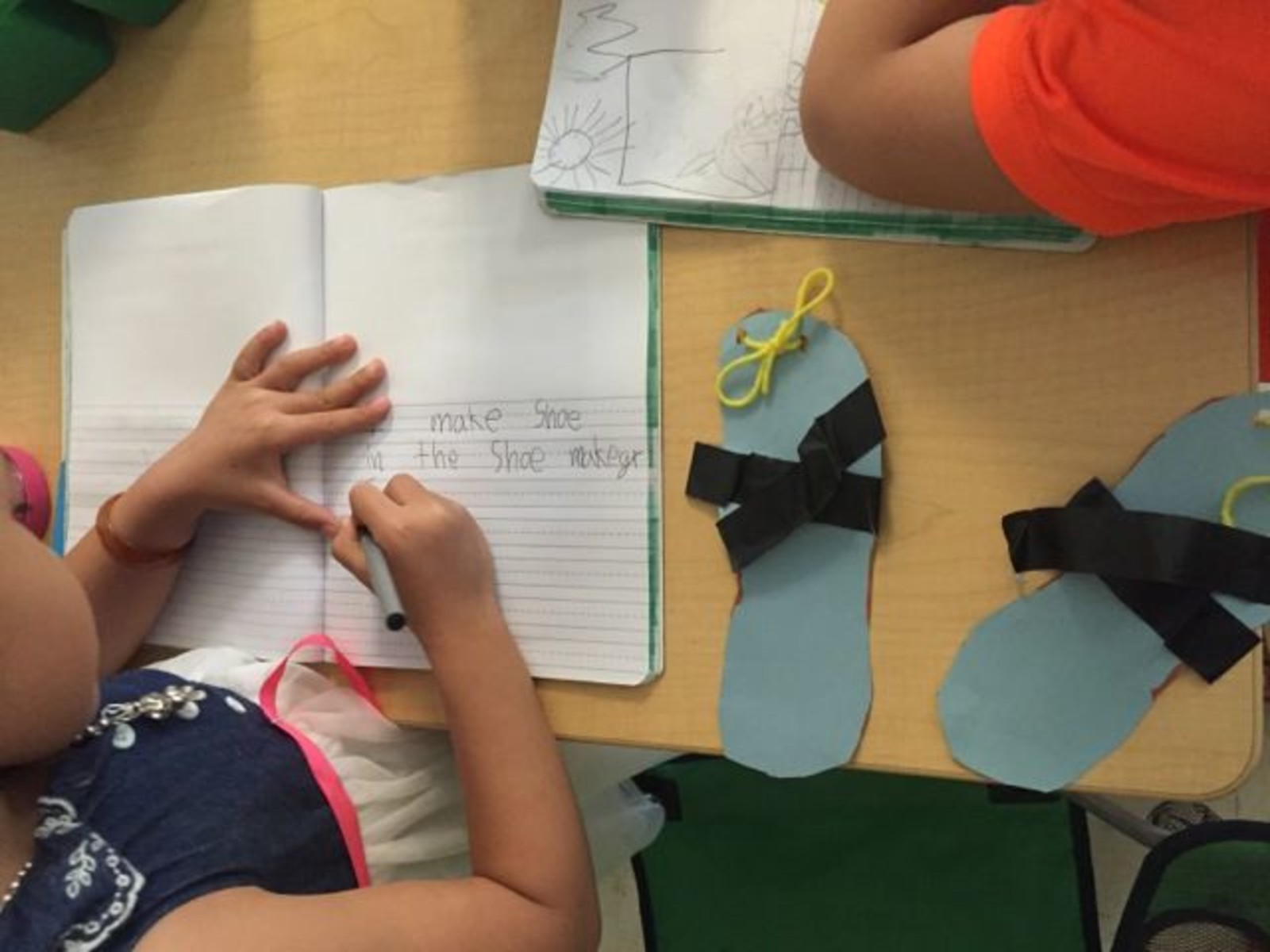

One day last school year, a girl in Fanny Roman's kindergarten class at PS 244 in Flushing, Queens arrived bubbling with excitement about her new shoes. With Roman's encouragement, she began tracing classmates' feet on paper and constructing "shoes," using pipe cleaners for laces. Her enthusiasm proved contagious; in response, Roman read poetry and picture books about shoes and students set up a play shoe store of their own, with different-size shoes in boxes, labeled "Jellies" or "Sneakers," as they categorized by size and even priced their wares. In their writing, they started using words such as "Velcro," buckles" and "shoelaces."

Welcome to "choice time." In a number of New York City elementary school kindergarten classes, it revives, in modified fashion, the once-common play-as-learning "free time" that's been driven almost to extinction in favor of whole-class instruction, textbooks, worksheets, and other elements of more rigorous education in the Common Core era.

Nationally, the amount of kindergarten time spent on reading and math instruction has substantially increased, according to a recent study published by AERA Open, titled, "Is Kindergarten the New First Grade?" Authors Daphna Bassok, Scott Latham and Anna Rorem found that some 80 percent of a national sample of teachers now believe students should learn to read in kindergarten, compared to only 31 percent who thought that in 1998; only 40 percent reported at least an hour of student-driven activities per day in their classrooms.

While there's no question that early education is critical, there's also a growing number of researchers, educators and parents questioning whether the formal academic approach now rooted in many kindergarten classrooms has gone too far.

Academic expectations and play don't have to be mutually exclusive goals, some early childhood experts say. Lilian G. Katz, author of Lively Minds: Distinctions Between Academic versus Intellectual Goals for Young Children, argues that while "bits of information," such as learning the sound of the letter "s," do matter, they may not warrant as much time as schools increasingly give them. She and other prominent educators, including Deborah Meier and Nancy Carlsson-Paige, are part of a nonprofit group called "Defending the Early Years," intended to help early childhood educators combat an increased focus on academics over the discovery, inquiry and play that stimulates the mind in a fuller way and is often called "choice time."

Another highly respected, now retired, elementary school teacher in New York City, Renée Dinnerstein, believes that a way to stimulate a rich choice time is to "make the classroom into a sort of laboratory for children—to create a science center where they really feel like scientists; an art center where they really feel like artists."

"The challenge," she says, "is to plan inquiry-based, explorative choice time, acknowledging important elements of free play within the high standards expected" in the Common Core–era classroom—even in kindergarten.

Dinnerstein expands on these ideas on her blog, "Investigating Choice Time: Inquiry, Exploration and Play," and in a new book, Choice Time: How to Deepen Learning through Inquiry and Play, Pre-K–2 published by Heinemann Press. In recent years, she also has helped develop kindergarten choice time at various local schools.

"The teacher's prepared environment is essentially what differentiates free play and choice time," Dinnerstein says. That can mean, for example, creating a classroom "construction area" replete with kid-sized safety goggles, vests, blocks, hard hats, sign-making materials and mini-people or animals. Teachers introduce items of interest based on what kids say and do.

PS 244 principal Bob Groff says that for his students (drawn from a heavily Chinese immigrant neighborhood where some 70 percent start school with little or no English) "choice time is a great opportunity to develop language socially and academically at the same time." It also encompasses reading, writing and math learning goals. "This blends all of that together," he said. "It's natural, not forced. It's going to have more long-lasting success."

Kindergarten teacher Fanny Roman is a believer in choice time, too, and has put it at the start of the school day. "I liked it first thing," she said. "It made me so excited every day to come in." Nevertheless, choice time also takes time—time that isn't easy to find. "Every minute counts," said Roman. "It's all about the testing grades and what we have to do to get them ready in kindergarten."

Dinnerstein thinks those minutes could be used better—to create an intellectually stimulating kindergarten that promotes reasoning, analyzing, predicting and questioning. "When kids are pushed to read early, they're not pushed to do a lot of thinking," she said. "It's not like I'm against children learning to read. [But] I don't think the goal is that every child leaving kindergarten has to learn to read. If you have two children in one family, they're not learning everything at the same speed—crawling, pushing up, standing—but they all end up walking."

This article also appears on the Urban Matters blog, Center for NYC Affairs.

Please Post Comments