Fitness Focus: Better fitness leads to better test scores

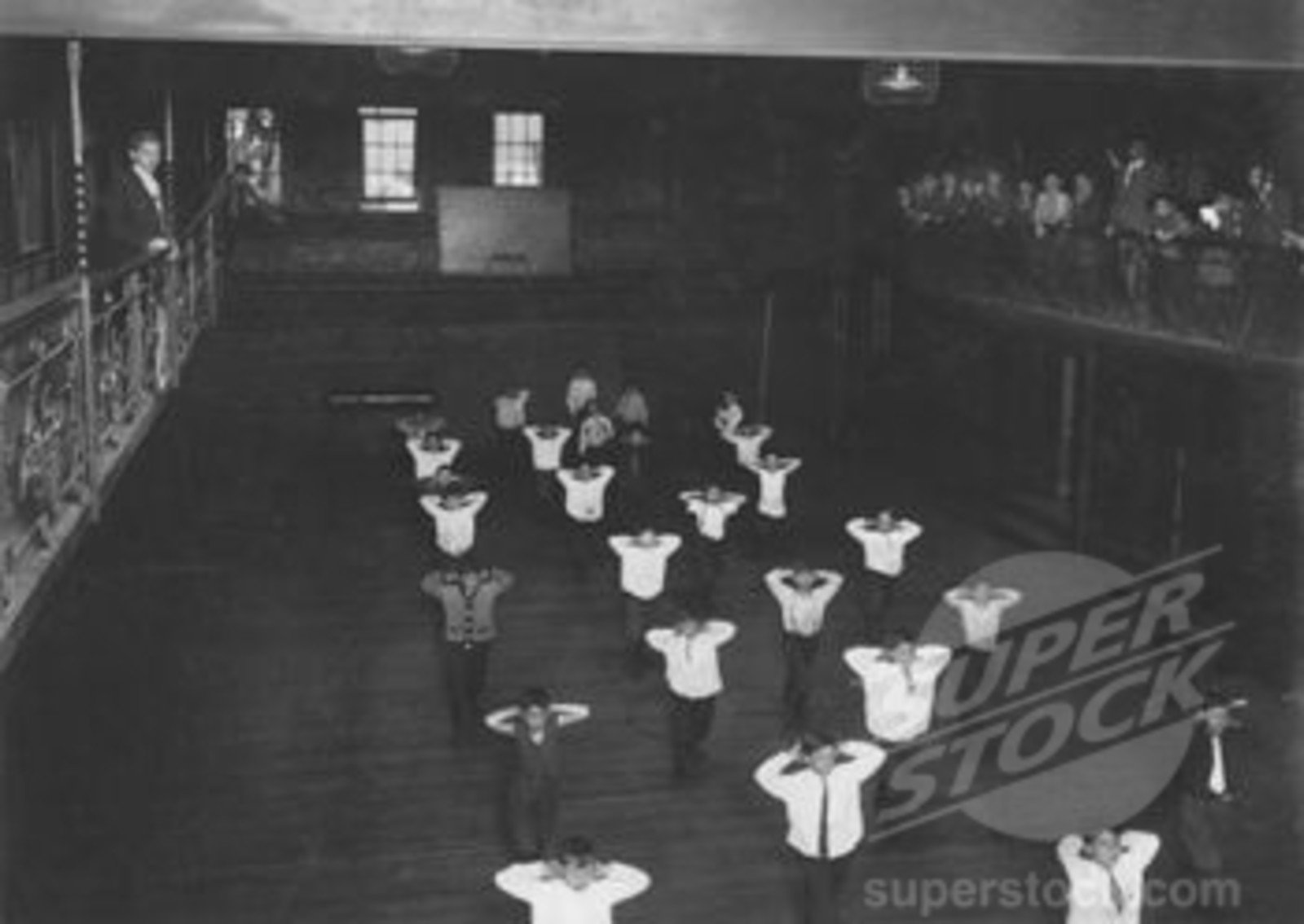

That was then: Henry Street Settlement gym class, 1910. - via leposters.com

That was then: Henry Street Settlement gym class, 1910. - via leposters.com

In recent years, many schools have cut gym time in an attempt to focus more on academics. But research shows they should be doing the opposite: Better fitness means better performance on academic tests.

Studies in California, Philadelphia, Massachusetts and New York City bear this out: "Results indicate a consistent positive relationship between overall fitness and academic achievement," a 2005 California study reports. "That is, as overall fitness scores improved, mean achievement scores also improved." (Much more research is cited on the International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity.)

The gym class most of us remember--or would like to forget-- consisted of "useless" drills, after which natural athletes made the varsity while "the rest of us watched," UCLA public-health scholar Dick Jackson told me recently. That kind of class doesn't help much. But techniques that improve fitness for everyone - which more and more PE teachers use- have an important role.

I described the importance of phys ed programs to students' health in my first post. But where are they supposed to happen? Consider these statistics compiled about Bronx public schools, attributed to former borough president Adolfo Carrion: "... 23 percent of Bronx schools have no indoor gyms: 22 percent have no outdoor facilities: 25 percent have no certified physical education instructors, and 90 percent of elementary schools and 50 percent of secondary schools failed to ...meet minimum state-mandated physical education requirements."

Lori Rose Benson, head of the DOE's Office of School Wellness Programs, faces the formidable task of helping 1.1 million kids incorporate exercise into their daily lives when no school can offer gym class every day. She's doing it by focusing on clever scheduling, offering a wide variety of sports, and training teachers to make every minute count.<!--more-->

"Prior to this administration there hadn't been a systemic way of supporting PE after the fiscal crisis of the late 1970s," Benson told me. "When I started in 2003, 75 percent of elementary schools had at least one PE teacher. That has grown to 92 percent, because there are folks within our system talking to principals about what's realistic in scheduling."

Benson and her team have joined forces with the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. They imported and adapted programs like CHAMPS and NYC FITNESSGRAM that measure student health and encourage students to find sports they enjoy. And, says Benson, they made pincer attacks on the daily schedule. "DOHMH bought a curriculum through [City] Council money, and we got a grant from Nike to use the Spark curriculum," Benson said. The Spark curriculum helped DOE "train upwards of 2000 teachers to think about how they can insert small fitness breaks into the day."

Some might call this triage. But if it helps school leaders focus more on fitness outcomes than merely on minutes spent in gym class, a training-heavy approach can break old stereotypes. For now, statisticians at the health department are finalizing a 2009 study that shows a distinct positive correlation- a line drive, one might say- from improvements in NYC FITNESSGRAM scores to improvements in academic test scores.

Here's hoping Benson and her team can use that finding to secure more training dollars to help PE teachers establish themselves as key players on the learning squad.

Please Post Comments