From LEGO to underwater robotics: Coney Island teachers create marine science "pipeline" for students

Originally posted on Chalkbeat by Monica Disare on June 27, 2016

When people think of Coney Island, they often picture a beachline with brightly colored roller coasters and hot dog stands, but high school teacher Lane Rosen sees it a laboratory for the next generation of marine scientists.

"People don't realize there's 567 miles of coastline in New York City," Rosen said. "There's tens of thousands of jobs, but we're not training anybody for any of them."

Rosen and a group of teachers in Coney Island have a radical plan to transform education in their neighborhood: build a marine science pipeline that helps guide a student all the way from the first day of elementary school through college or into a career.

The plan tackles an issue that has befuddled educators for years: How do you ensure students have a clear way to stay on track from the beginning to the end of their education? It also invests heavily in career-focused learning, which is in line with the city's push to expand and strengthen CTE programs.

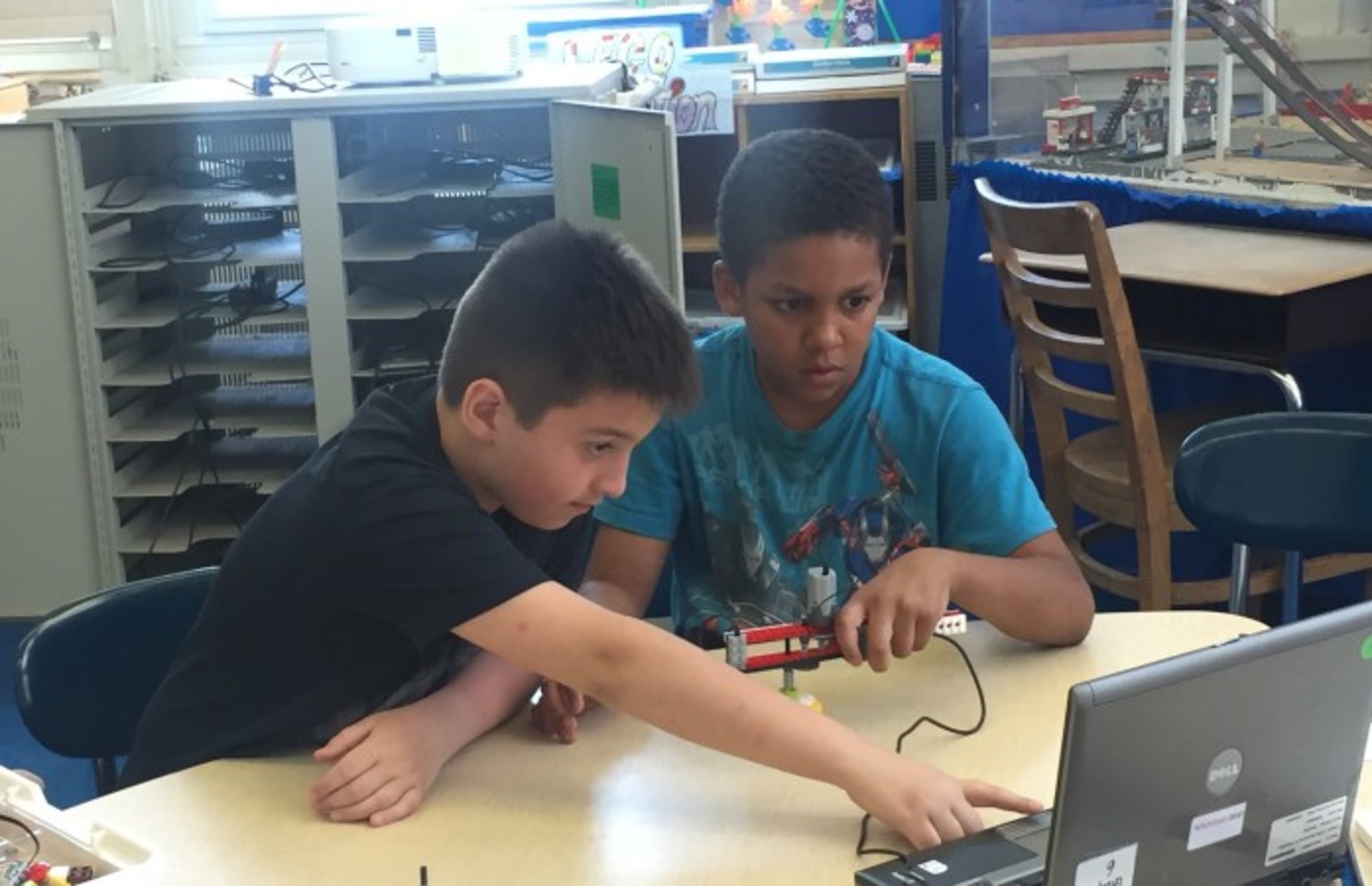

Students at PS 188, a local elementary school, are already encountering a science-heavy curriculum that includes basic coding and experimenting with lego robotics. In middle school at IS 281, the goal is for them to move onto advanced robotics, and by the time they reach John Dewey High School, teachers can tie in marine science and technology.

Why stop at high school graduation, though? The group of teachers is starting to forge relationships with Kingsborough College, which has a maritime technology program, and even with the local divers union.

"We have a whole curriculum that was written in terms of going from step 1, to step 2, to step 3, to step 4, to step 5," said Scott Krivitsky, a kindergarten teacher at PS 188.

The project, which began in earnest last year, remains a somewhat loose collection of schools trying to define what it means to be a "pipeline." In addition to PS 188, IS 281 and John Dewey High School, Krivitsky says other schools are getting involved. There are around 30 schools interested in the initiative, known as the Brooklyn Marine STEM Education Alliance. Aside from academics, the group also organizes out-of-school events, such as beach cleanups.

Teachers know a fully-fledged pipeline faces a number of challenges. There is no way to ensure that students remain in the same set of schools, or stay interested in marine science. Not to mention, no teacher wants to track a student into a specific career field starting in kindergarten.

But they are confident students will stick with the program because they are inspired by marine science and robotics, not because they feel boxed into a particular career.

"If all the schools work together, STEM is just a hook," said high school robotics teacher Fil Dispenza.

That theory was on display at PS 188 on a recent Wednesday afternoon. A group of fourth-grade students stared intently at their computer screens, trying to program a spinning top made of legos. One-by-one they watched their projects come to life.

"One Mississippi, two Mississippi," they counted in unison, transfixed by the spinning gears.

While the project doesn't have an obvious marine science tie-in, it's the kind of work that lays an early foundation for more advanced scientific thinking.

As the students advance, the curriculum delves more deeply into marine science, a subject Coney Island students can relate to since they live in a coast town, Rosen said. That became crystal clear in the wake of Hurricane Sandy. The elementary school, which was temporarily shut down after the storm, is still dealing with repairs. The high school had flickering electricity for a year and a half and some teachers lost their homes, Rosen said.

"I hate to say this, but this disaster, or travesty, really makes my classroom — it makes it alive," Rosen said, "because I have something to refer to that the kids know about."

If nothing else, connecting high schools with elementary schools helps inspire some of Brooklyn's youngest learners, said Uzma Harris, the technology teacher at PS 188.

In the corner of the elementary school's "lego lab," where students learn about robotics, is an expansive model of Coney Island, complete with roller coasters, a ferris wheel and a carousel. John Dewey High School students worked with elementary school students to build the model, which, in itself, represents the pipeline teachers are trying to create.

"When students come in they just gravitate towards this," Harris said about the model. " It just shows what they can do."

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.

Please Post Comments