How Over-incarceration of Parents Can Harm Children

By Leila Morsy and Richard Rothstein

As many as one in 10 African American students has an incarcerated parent. One in four has a parent who is or has been incarcerated. The discriminatory incarceration of African American parents is an important cause of their children’s lowered performance, especially in schools where the trauma of parental incarceration is concentrated.

Two policies have been mostly responsible: an increasingly punitive sentencing policy, including prison terms for violent crimes that have increased by nearly 50 percent since the early 1990s; and the declaration of a “war on drugs” that has included severe mandatory minimum sentences for relatively trivial victimless drug offenses. The incarceration explosion is primarily an expression of our race relations and of the confrontational stance of police toward African Americans in neighborhoods of concentrated disadvantage. (The incarceration rate of middle-class African Americans has declined and makes no contribution to the rapidly rising rate of incarcerations.) Young African American men are no more likely to use or sell drugs than young white men, but they are nearly three times as likely to be arrested for drug use or sale; once arrested, they are more likely to be sentenced; and, once sentenced, their jail or prison terms are 50 percent longer, on average.

Educators have paid too little heed to this criminal justice crisis. Criminal justice reform should be a policy priority of educators who are committed to improving the achievement of African American children.

Children of incarcerated parents suffer serious harm. It is tempting to think that these consequences are attributes of disadvantaged children, independent of parental incarceration. But careful studies of the effects on children have accounted for these attributes. Children of the incarcerated have worse cognitive and non-cognitive outcomes than children with similar socioeconomic and demographic characteristics whose parents have not experienced incarceration.

Such research shows that:

• Children with incarcerated parents are 33% more likely to have speech or language problems – like stuttering or stammering – than otherwise similar children whose fathers have not been incarcerated. The grade point averages of children with incarcerated parents decline.

• It is more common for children of incarcerated parents to drop out of school than it is for children of non-incarcerated parents, controlling for race, IQ, home quality, poverty status, and mother’s education. This is especially true for adolescent boys between the ages of 11 and 14 with a mother behind bars. Such boys are 25% more likely to drop out of school, and they are 55% more likely to drop out of school because they themselves have been incarcerated.

• Children of incarcerated fathers complete fewer years of school than children of non-incarcerated fathers, controlling for other likely confounding social and demographic characteristics.

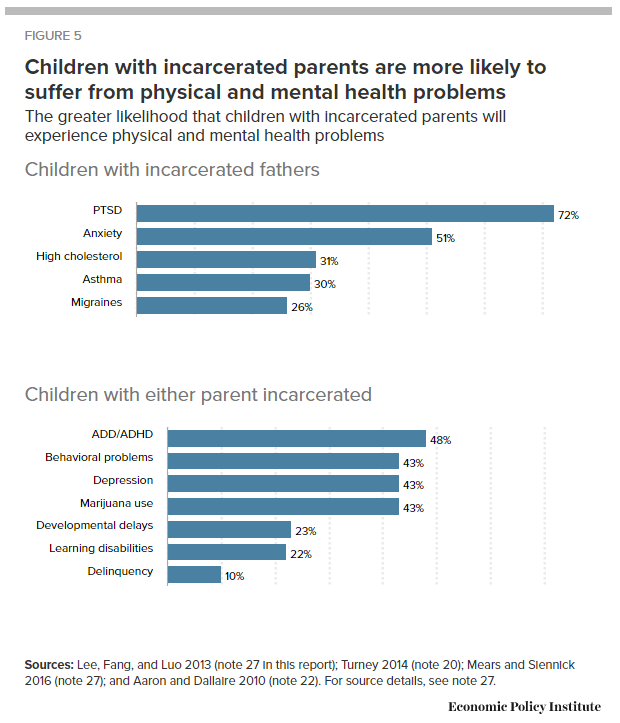

• Children with incarcerated parents are 48% more likely to have attention deficit disorder than children with non-incarcerated parents. They are 23% more likely to suffer from developmental delays. Children with incarcerated parents, especially sons of incarcerated fathers, are 43% more likely to suffer from behavioral problems. These differences show up in comparisons of otherwise similar children.

• Children of incarcerated fathers suffer from worse physical health. They are a quarter to a third more likely than children of non-incarcerated fathers to suffer from migraines, asthma, and high cholesterol.

• Their mental health is also worse than that of children of non-incarcerated fathers. Children of incarcerated fathers are 51% more likely to suffer from anxiety, 43% more likely to suffer from depression, and 72% more likely to suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder.

• As adults, daughters of parents who have been incarcerated have a higher body mass index, which is associated with other health problems, such as heart disease and diabetes.

• Children of incarcerated parents are more likely to engage in behavior that exposes them to the criminal justice system. They are 43% more likely than socially and demographically similar children of non-incarcerated parents to smoke marijuana. They are 10% more likely to turn to delinquency than children without incarcerated parents.

Children’s cognitive and non-cognitive problems, to which parental incarceration contributes, and the concentration of children of incarcerated parents in low-income minority neighborhoods and in segregated schools create challenges for teachers and schools that are hard to overcome. Ending the “war on drugs” and the resulting mass incarceration of fathers of schoolchildren, and other criminal justice reforms, should be a priority for educators who are committed to improving the achievement of African American children.

While reform of Federal policy may seem implausible in a Trump administration, educators can seize opportunities for such advocacy at state and local levels. In 2014, over 700,000 prisoners nationwide were serving sentences of a year or longer for nonviolent crimes. Over 600,000 of these were in state, not Federal, prisons.

We will be discussing our findings on these issues in a forum held at the Economic Policy Institute on March 15 at 10:30 a.m. U.S. Eastern Standard Time. Valerie Strauss, the online education columnist (“The Answer Sheet”) of The Washington Post, will moderate the forum, and our presentation will be discussed by Glenn Loury of Brown University and Ames Grawert of the Brennan Center for Justice. It will be livestreamed here and available for viewing at the same site after the event.

Leila Morsy is a senior lecturer in education at the School of Education, University of New South Wales, and a research associate of the Economic Policy Institute. Richard Rothstein is a research associate of the Economic Policy Institute and a senior fellow at the Thurgood Marshall Institute of the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund.

This is a condensed and lightly edited excerpt, presented with their permission, from their December 15, 2016 report for the Economic Policy Institute, “Mass Incarceration and Children’s Outcomes: Criminal Justice Policy Is Education Policy.”

This article originally appeared on the Urban Matters blog, Center for New York City Affairs.

Please Post Comments