How the city can ease parents’ fears about integration

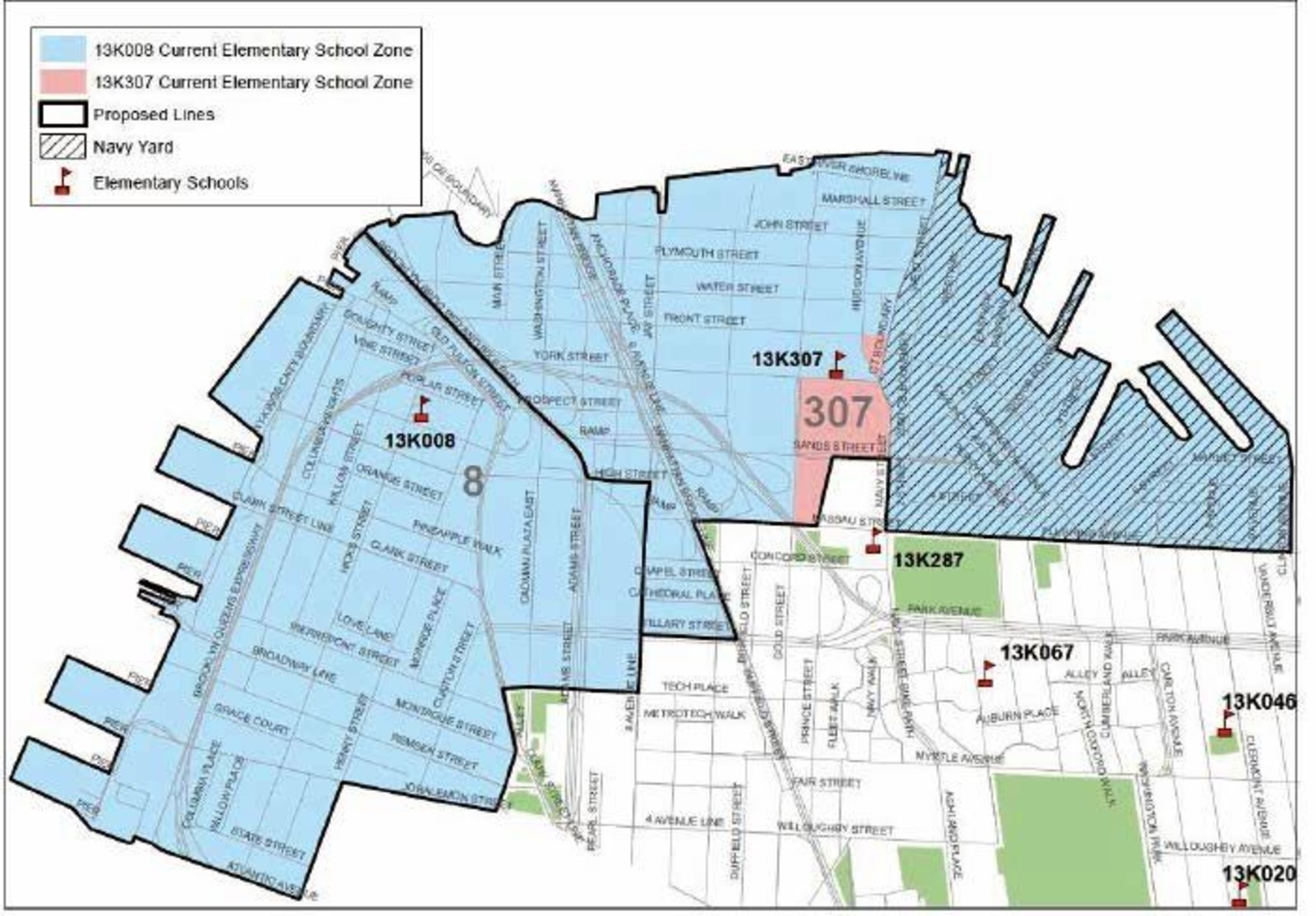

On paper, the rezoning plan makes a lot of sense: PS 8 in Brooklyn Heights (which is 60 percent white) is very overcrowded and nearby PS 307 (which is 90 percent black and Latino) has room to spare. So why not shrink the PS 8 zone—one of the largest in the city—and enlarge the PS 307 zone—now a tiny speck that includes the Farragut housing projects—to make room for future growth in the school-age population?

Unfortunately, the Department of Education has done a lousy job presenting the plan to the District 13 Community Education Council (the elected panel that must approve any zoning changes) and parents in both school zones worry about what the changes mean for their children. If the plan is going to be successful, officials must do a much better job at the next CEC meeting on September 30, explaining what the benefits might be for everyone involved. Just as important, the city must commit the staff and resources necessary to address parents’ legitimate fears.

Some PS 307 parents worry that a community institution that has long nurtured black and Latino families will be “taken over” by outsiders. Will the new PTA be dominated by wealthy whites who organize fancy auctions that current parents can’t afford to attend? Will the administration cater to the newcomers, neglecting the concerns of the neediest children?

For their part, some parents in the current PS 8 zone fear that their concerns will be neglected if their children are assigned to PS 307. Will the academics be challenging at a school where just 12 percent of students met state Common Core standards for reading this year (compared to 64 percent at PS 8)?

At two public meetings this month, officials from the office of district planning presented maps and charts with enrollment projections—but nothing to explain how the plan would affect the academic life and culture of PS 307. Even parents who support the plan say the rollout has been poor.

Finding a solution that addresses everyone’s concerns won’t be easy, but there are steps school officials can take.

First, officials need to point out that any changes will be gradual: Current PS 8 pupils will stay at their school. The changes only affect new kindergartners. It’s unlikely that PS 307 will be swamped with newcomers.

Second, parents need to hear from a seasoned educator—not someone from the office of district planning—about plans for the school. The current principal, the superintendent, and maybe even the chancellor can reassure current and prospective parents about practical things like the size of the budget (which will grow with enrollment) and class size (which is small and could stay small, given the space in the building). Parents need to hear from the principal how she might mediate between different cultures and expectations. What happens if some parents want kids to wear uniforms and others want them to wear jeans? Or if some want outdoor recess and others want to keep children inside in the winter?

School officials need to explain the concrete ways in which they can give the necessary attention to children with a wide range of academic skills, perhaps by assigning two teachers to some classrooms. And officials should publicly commit to continue the school’s successful programs, such as the magnet grant that provides every child with three hours a week of hands-on math and science—and attracts children from other Brooklyn neighborhoods like East New York and Bedford Stuyvesant.

Informal meetings of future and current PS 307 parents can also help. The public meetings tend to attract vocal opponents, but parents who want to come up with solutions are better served at quiet gatherings. Luckily, the debate isn’t completely polarized. Both black and white parents at the meetings spoke of the need to work together.

PS 307 has many strengths. Longtime principal Roberta Davenport, who retired in June, built a school where teachers trust one another and parents feel valued. The new principal, Stephanie Carroll, is poised to carry on her legacy. In addition to the math and science magnet grant, the school has lots of special programs such as Mandarin classes and violin lessons. A well-regarded special education program offers intensive help to children on the autism spectrum, and staff are well-trained in how to deal with children’s social and emotional problems.

At the same time, the school has enormous challenges. Nearly one-third of children receive special education services—twice the proportion of PS 8. The school has a high rate of chronic absenteeism: One-third miss more than a month of school each year. Test scores are low—as they almost always are in schools in which families come and go throughout the year.

Rezoning PS 8 and PS 307 is a historic opportunity to begin to end the intense segregation that has long plagued the New York City public schools. Similar debates are going on in other gentrifying neighborhoods in the city, and a successful plan that takes into account the needs of all parents can be a model for others. But without careful planning, anger and fear will prevail.

Please Post Comments