Pre-k expansion may suck life out of EarlyLearn

It's crunch time for pre-kindergarten. In just a couple of weeks, the city will open 2,000 new, full-day classrooms in schools and community centers across the five boroughs. If the city gets it right, the pre-k expansion could set a national standard for universal, high-quality instruction for 4-year-olds. Unfortunately, it could also be the cause of death for programs serving those 4-year-olds' younger siblings.

Though it has stood alone in the political spotlight this year, universal pre-k is not New York City's only early education program. For decades, the city has held contracts with hundreds of childcare providers—ranging from home-based daycares to nationally accredited preschools—to care for low-income kids from 6 weeks through 4 years old. In its current iteration, the subsidized childcare system has the capacity to serve 37,000 children.

National studies show that early childhood programs are critical for kids. The care a child receives while she's an infant or toddler—long before she's old enough to go to school—can impact the way her brain grows, potentially changing the trajectory of the rest of her life.

Studies also show that most low-income kids receive dismal out-of-home care. In one massive dataset published by the National Center for Education Statistics, 96 percent of home-based daycare arrangements serving kids under the poverty line rated as poor or mediocre. In New York City, the quality of subsidized childcare programs has historically been all over the map: Some kids are taught by credentialed teachers in classrooms designed to foster social skills and early literacy; some spend their days watching videos.

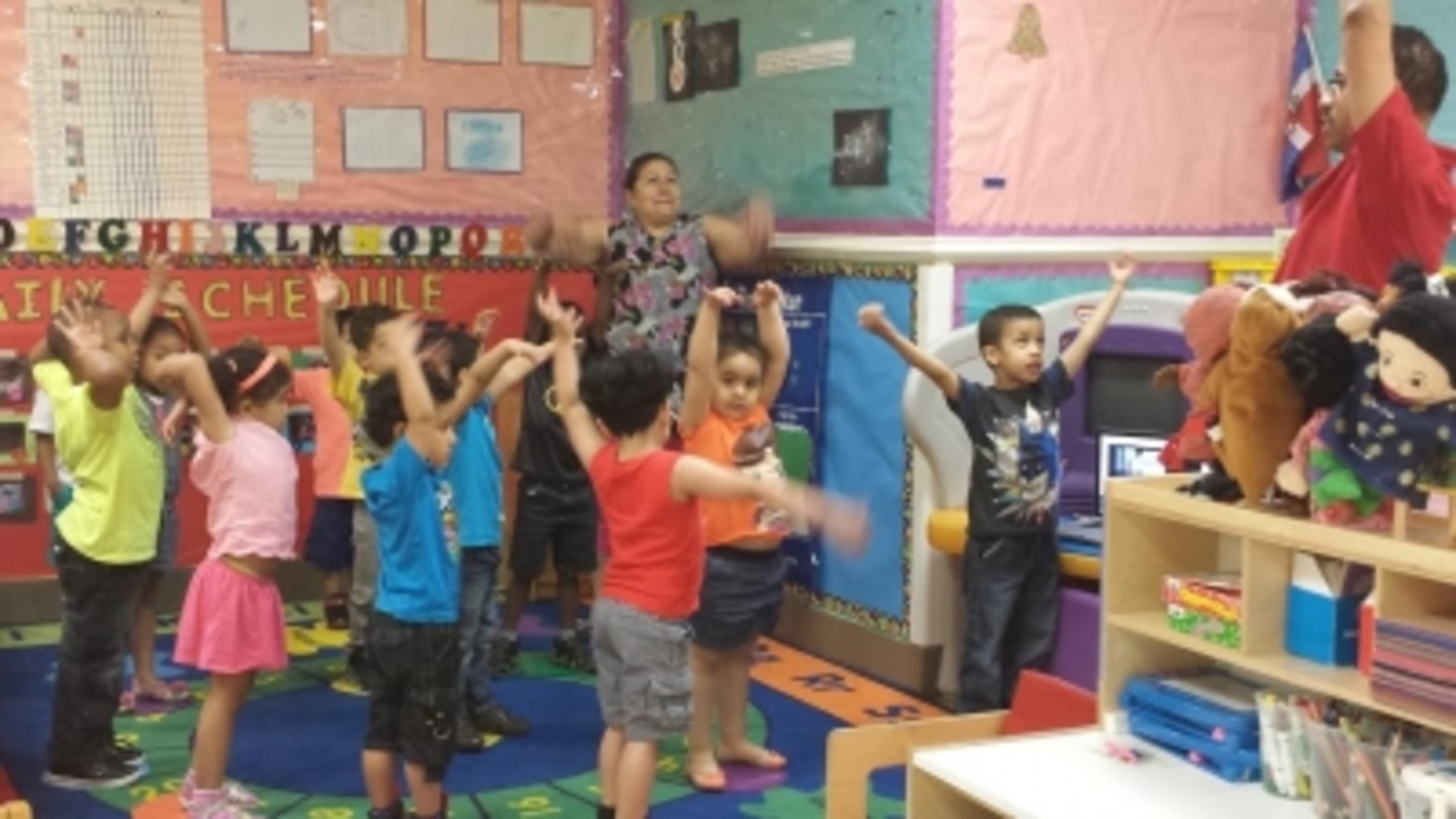

In 2012, the city invested close to $500 million to overhaul its subsidized childcare programs. The vision was transformative: Under the newly reformed system—known as EarlyLearnNYC—every city-funded program would use a research-based curriculum, proven to support children's learnin, as we explain in a new report by the Center for New York City Affairs at the New School. Teachers would get ongoing training. Programs would work with families to help them overcome obstacles like homelessness or domestic violence, which threaten to hold their children back. By the time kids turned 5, the hope went, they'd be prepared for success in kindergarten and all the years that come after.

Two years later, the reality of EarlyLearn has fallen far short of its goals—mostly due to a list of prosaic and predictable causes. The program didn't get all the funding its planners expected. Staff are poorly paid, making it difficult for providers to find qualified teachers. There's been no money to update the city's antiquated referral system, so even very high-quality programs are left with empty seats. When families do find their way to an EarlyLearn provider, the city can take so long to approve a child's enrollment that many parents walk away.

Because child care programs (unlike public schools) are only reimbursed for the number of kids sitting in their classrooms, even a few missing children can make it impossible to meet fixed expenses like payroll and rent. Many EarlyLearn programs are struggling just to keep their doors open.

And now—in an ironic twist of political fate—the city's expanded pre-k program threatens to suck the remaining life out of subsidized childcare.

The most pressing danger is an exodus of qualified teachers. Under the new pre-k plan, teachers will start at a salary of up to $14,000 more per year than they earn in the EarlyLearn system, and many will work shorter days, with summers off and better benefits. EarlyLearn directors say that new pre-k programs are aggressively recruiting their best teachers. Who could blame them for leaving?

New pre-k classrooms will also create more competition for kids. EarlyLearn providers who already serve 4-year-olds will get some funding to adjust their programs, but they remain hobbled by the bureaucratic inefficiencies built into the subsidized childcare system. In a particularly egregious example, the city still hasn't told programs what they'll be required to charge parents for care after the school day is done. "Parents are asking basic questions and we don't have answers. We feel ridiculous," says one EarlyLearn director in the East New York neighborhood of Brooklyn. "We could find ourselves with empty classrooms in September."

Expanded choice will undoubtedly be a good thing for 4-year-olds and their families, but the city is failing to give parents any reason to choose the EarlyLearn programs into which it has already invested so many taxpayer dollars. Without 4-year-olds to fill their classrooms, many EarlyLearn programs will sink. Who will be left to care for babies and toddlers? What will happen to the feeder system for universal pre-k?

The good news is that subsidized childcare is not beyond salvation. The city has already made a commitment to early education. Now it must broaden its focus from expanding pre-k to creating a holistic system, serving children from birth until they're old enough to go to school. With an infusion of resources and attention, EarlyLearn could work in tandem with the city's new pre-k classrooms to create one of the most sophisticated early childhood systems in the country.

Isn't that what our kids deserve?

Please Post Comments