Why can’t we have great schools in every neighborhood?

The problem with public education in America isn’t that all schools are bad. The problem is that the quality is so uneven. In New York City, some lucky parents simply enroll their children in their neighborhood school with nothing more than proof of address. But many parents, unsatisfied with their local schools, scramble to find other options—often far from home.

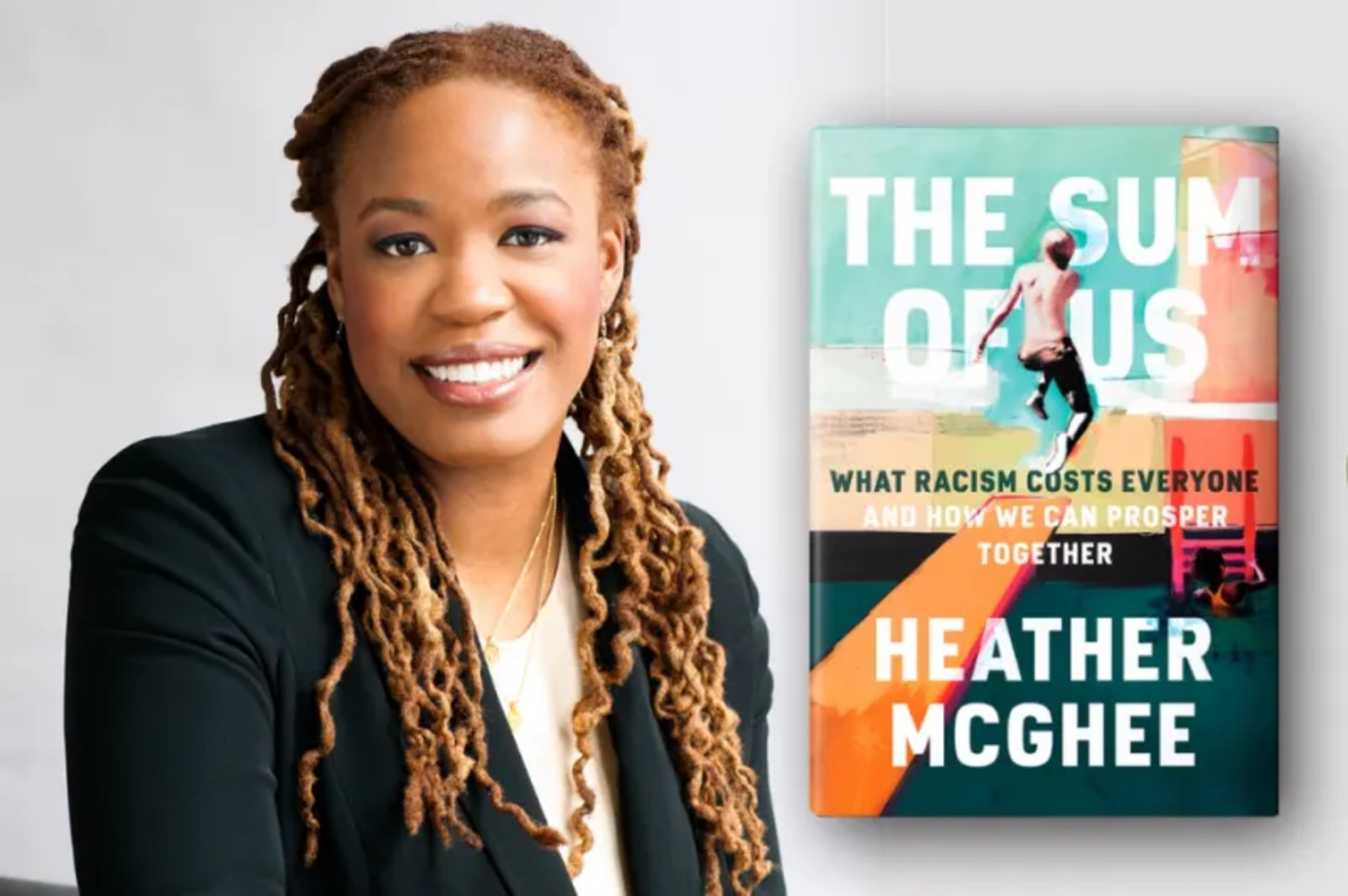

So why can’t we have great schools in every neighborhood? Heather McGhee poses that simple but confounding question in The Sum of Us: How Racism Hurts Everyone. This book, published in a longer version in 2021, has just been released in an edition adapted for young readers. There’s also an 8-episode Sum of Us podcast.

The answer, McGhee argues, is racism, which pits people of different races against one another and keeps us from working together. And, she says, while racism hurts people of color the most, there is also a cost for white people—not just in education, but in other areas of public life.

She gives the example of public swimming pools. In the 1920s and 1930s, cities and towns across the country, with the help of the federal government, built thousands of public swimming pools—most segregated by race. During the Civil Rights movement, Blacks campaigned to be allowed access to these pools. But rather than permitting integration, city officials in places like Montgomery, Alabama, drained the pools, filled them with dirt, and paved them over. Racism deprived Black children of a free place to swim, McGhee says. But it also deprived white children of a public good.

In schools, McGhee argues, racism hurts just about everyone. Public education is mostly financed through local taxes, so the richest suburbs (where Blacks have historically been excluded) can afford to spend the most on their local schools. Other cities and towns struggle to raise tax revenue for education. This hurts people of color, but it hurts white families as well. White families may stretch their budgets to pay for overpriced housing in “good” (or at least very expensive) school districts with overwhelmingly white enrollments. McGhee calls this a “tax on racism” that most people can’t afford.

The solution is what McGhee calls the “solidarity dividend.” Her book and podcast tell stories of people who have worked across racial lines to improve conditions for everyone, from fast-food workers in Kansas fighting for higher wages to citizens in Memphis who discovered a common interest in preserving clean drinking water.

In New York City, I’ve long observed parents compete against one another for what they see as a scarce resource: seats in a “good” school (or at least one with high test scores). These parents see quality education as a zero-sum game. There are only so many seats to go around. For my child to win, your child must lose.

It doesn’t have to be this way. The “solidarity dividend” can work here too. For example, at Brighter Choice Community School, a neighborhood elementary school in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn, parents of different races and income levels are learning to work together to support their school. Instead of leaving their neighborhood in search of a “good” school, these parents are helping to build a good school close to home. It’s not easy, as I show in my new book, A Brighter Choice: Building a Just School in an Unequal City, to be published next month. Hurt feelings and misunderstandings drive parents apart. There are problems outside the school’s control—such as high rates of homelessness that make it hard for children to succeed. But parents at Brighter Choice work for the common good, not just for what will benefit their own children. It’s a small step toward building great schools in every neighborhood.

Please Post Comments